Gender

Although age and other factors play a stronger role in influencing HRV than gender, notable gender dependencies of short-term HRV indices have been observed.

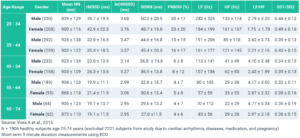

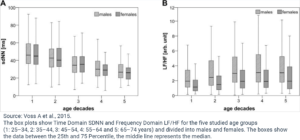

The study “Short-Term Heart Rate Variability—Influence of Gender and Age in Healthy Subjects,” by Voss A et al. (2015) shows that males typically have lower Heart Rate Variability than females within the same age ranges. This indicates that males exhibit stronger Sympathetic (fight-or-flight stress response) tendencies over Parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) than comparable females.

Males typically have lower Heart Rate Variability than females within the same age ranges. This indicates that males exhibit stronger Sympathetic tendencies over Parasympathetic.

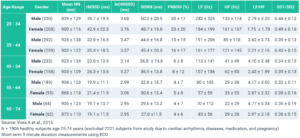

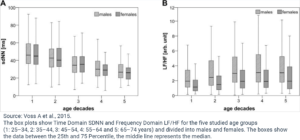

In the study, the short-term (5 minute ECG/EKG measurements) HRV indices for 1,906 healthy individuals aged 25 – 74 years were analyzed to determine gender and age effects on HRV. The results showed that women under age 55 exhibit higher HRV time-domain values for RMSSD, PNN50, and, higher HF and lower LF and LF/HF ratio than men in comparable age ranges. In particular, the notably higher Time Domain RMSSD, lower Frequency Domain LF/HF ratio, and lower Poincare SD1/SD2 in females below the age of 55 demonstrate the increased Parasympathetic dominance.

How do you compare to your age-gender demographic?

Age and Gender

Interestingly, the gender-related variation in HRV decreases over the age of 55 years. The major age-related HRV differences for both genders are between ranges 35–44 years and 45–54 years. The study suggests that the gender-related HRV differences in the younger ages is probably caused by “the different hormonal situations leading to a higher sympathetic activity and a lower parasympathetic tone in men and vice versus in women”.

Gender-related variation in HRV decreases over the age of 55 years.

Furthermore, when comparing age groups 45–54 years and 55–64 years, females have significantly higher HRV differences compared to males, which corresponds to age-related hormone effects (menopause). The gender-related HRV differences disappear with aging because of the “hormonal restructuring” such as menopause in women and other hormonal changes in men that occur with aging and lead to more “comparable hormonal stages” in the gender groups above age 55. Some other studies show that declined estrogen levels associated with the Autonomic Nervous System changes seen in postmenopausal women (Moodithaya et al., 2009) and increased total HRV and baroreflex sensitivity in postmenopausal women with hormone replacement therapy (Pikkujämsä et al., 2001) suggest that hormonal factors play a role for the observed age and gender related differences.

As can be seen from the data and discussed earlier, age strongly influences HRV, regardless of gender. Time Domain HRV indices decline and Frequency Domain LF and HF decrease while the LF/HF ratio increases with increasing chronological age for both genders (Agelink MW et al., 2001, Yukishita T et al., 2010, Greiser KH et al., 2009, and Felber Dietrich D et al., 2006). This age-dependent and gender-independent change to HRV indicates diminished Parasympathetic activation with increasing age.

Age-dependent and gender-independent change to HRV indicates diminished Parasympathetic activation with increasing age.

Considerable loss of heart beat variability and complexity could mainly be caused by cardiovascular structural changes through the loss of sinoatrial pacemaker cells or decreased arterial flexibility and functional changes in other regulatory processes that occurs during aging (Ferrari AU et al., 2002).

So, while gender does influence HRV values, especially in younger years, age has a greater contribution to HRV and overall health and resilience.

The Takeaway

If your HRV values are below your age-gender demographic range, then you may have underlying health concerns that are negatively affecting your biological age and should be addressed. Conversely, if your HRV values are regularly higher than your comparable age-gender demographic range, congratulations! Your biological age may be younger than your chronological age.

Keep in mind, there are exceptions for both above average and below average HRV cases, some of which are covered in Part 2 and Part 3 of this HRV Demographics series. Factors such as fitness level and physical and mental health can influence biological age and reflect in your Heart Rate Variability.

If your HRV values are below your age-gender demographic range, then you may have underlying health concerns that are negatively affecting your biological age.

In Part 2, we cover the impact that fitness has on your heart rate variability and how “fit” populations stack up against elite athletes and sedentary populations.

Did you know that aerobic fitness can actually mask underlying health issues? More on this in Part 2.