In Part 1: Age & Gender, we covered how age and gender can affect Heart Rate Variability and provided some normative HRV indices for different age-gender demographics. We also discussed that biological age, which can be measured by HRV, can be influenced by lifestyle factors such as health and fitness.

Aerobic Fitness

Aerobic fitness is one of the most controllable aspects of health and performance for everyone from young athletes to older health seekers. It also significantly impacts Heart Rate Variability values and contributes to better recovery, muscle regeneration, energy levels, immune function, memory, as well as many other beneficial processes in the body.

Generally, a higher Heart Rate Variability is correlated with increased aerobic fitness, and vice versa. This makes perfect sense since it is well established that regular aerobic physical activity can improve cardiovascular function and health which is measured indirectly through HRV.

Many studies have shown that the intensity, duration and frequency of aerobic training are directly related to HRV changes. This is why HRV analysis with respect to physical training, especially aerobic physical training, is an increasingly popular technology used by elite and recreational athletes to achieve an edge.

HRV analysis with respect to physical training, especially aerobic physical training, is an increasingly popular technology used by elite and recreational athletes to achieve an edge.

For most people, increasing aerobic fitness levels would be a favorable step for health, physical, and mental performance as would be reflected in increased HRV indices. However, the level of aerobic fitness that you require, and the method by which you achieve it, are very dependent on your goals and other individual factors such as your initial fitness level, gender, age, health, and genetics.

To better understand the effects of aerobic fitness level on Heart Rate Variability, we are going to dig deeper into the numbers comparing sedentary vs. active populations and active vs. athlete populations.

Sedentary vs. Active People

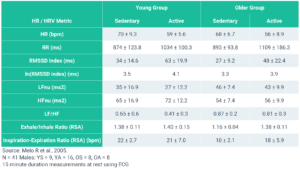

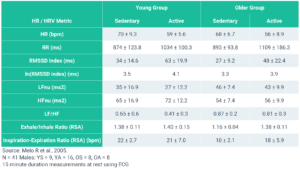

There is a significant difference in HRV values between sedentary and active populations for both males and females at different age ranges (Melo R C, 2005, Paschoal M A, 2008).

In the study analyzing sedentary vs. active young and older males, Melo et al. determine that the active sample groups had higher time domain RMSSD index and RR intervals and lower heart rates compared to the sedentary groups with similar anthropometric data (gender, age, height, weight, BMI.) Furthermore, “the older active group showed similar values for the RMSSD index in comparison to the young active group” (Melo et al., 2005). This indicates that the long-term physical activity performed by the older, active group contributed to their improved HRV indices over the sedentary group as they aged.

The study also measured RSA (Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia) indices via Heart Rate Variability during controlled breathing tests to evaluate autonomic nervous system dysfunction that occurs with aging. RSA is the naturally occurring respiratory-driven variation in heart rate linked to vagus nerve function (and therefore Autonomic Nervous System and heart health) through HRV measurement. RSA is known to decrease with age and health. For the active older males, the RSA indices were higher compared to the sedentary older males and closer in value to the younger males, suggesting that an active life pattern can be effective in diminishing the decline of HRV associated with aging.

Long-term physical activity performed by the older, active group contributed to their improved HRV indices over the sedentary group as they aged.

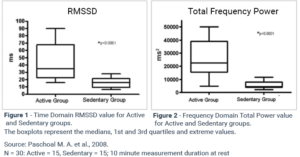

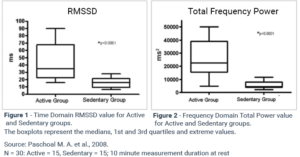

Similarly, in the study evaluating the effects of light aerobic physical activity on the Heart Rate Variability values of menopausal woman, Paschoal et al. determined that aerobic training may have caused significant improvement in autonomic cardiac function, as measured by HRV, for the active women.

To ensure comparable groups, none of the menopausal women were on hormone replacement therapy and had very similar age, weight, height, BMI, and Systolic/Diastolic blood pressure and many pre-test and test variables were controlled or accounted for. The active women had significantly higher Frequency Domain Total Power, Low Frequency power, High frequency power, and higher Time Domain average RR intervals, RMSSD, and PNN50 than the sedentary women indicating better cardiovascular health through autonomic cardiac and vagal activity improvement.

The good news is that in many of these studies, the activity level required to gain the significant health benefits as measured by Heart Rate Variability is only light to moderate. In the menopausal women study, the significant HRV improvement for the active women was seen at just light to moderate activity like walking three times per week for hour long sessions.

Both of these studies suggest that regular physical activity in the older subjects tended to reverse, to a degree, the aging effects on cardiovascular health such as vagal tone decline.

Regular physical activity in the older subjects tended to reverse, to a degree, the aging effects on cardiovascular health such as vagal tone decline.

Active People vs. Athletes

It is clear that an active lifestyle can significantly increase HRV over a sedentary lifestyle. So, how does a regularly active person compare to an athlete with high aerobic fitness level?

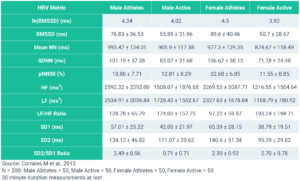

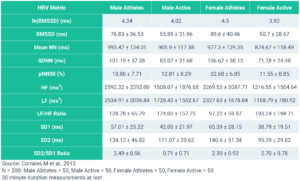

The following data is from a study comparing the normal values of Heart Rate Variability at rest in a young, healthy and active Mexican population. In the study, 200 participants between the ages 18-25 were divided into four groups:

- Male Athletes – Male athletes participating in collegiate sports with structured training at least 6 hours per week and competitions

- Female Athletes – Female athletes participating in collegiate sports with structured training at least 6 hours per week and competitions

- Male Active – Male participants that lead a generally active lifestyle but without structured sports training

- Female Active – Female participants that lead a generally active lifestyle but without structured sports training

The researchers concluded that significantly greater Heart Rate Variability was seen in trained men and women at rest, likely due increased vagal tone and parasympathetic activity and reduced sympathetic activity. Significant differences were found for most HRV Time Domain, Frequency Domain, and Poincare parameters between athletes and active subjects (male and female) but not between genders” within the same fitness level categories. This shows that fitness level has a greater contribution to HRV than gender effects (read more about how gender and age affects HRV in Part 1 of this HRV Demographics series).

Fitness level has a greater contribution to HRV than gender effects.

Interestingly, although there was not a significant difference between males and females with the same level of physical activity, the females did show the most benefit from the increased aerobic fitness with a greater difference between HRV values from the active level and the athlete level.

Endurance-Trained vs. Power-Trained Fitness

When most people think of aerobic fitness, they think of popular endurance sports such as cycling, running, triathlons, etc. Aerobic training in these sports in relation to HRV has been extensively researched. Although less studied, the available research shows HRV effects on anaerobically trained individuals in power sports to be similar to those of aerobically trained athletes (Berkoff D J et al., 2007).

In a study comparing 145 elite track and field athletes at the 2004 Olympic Trials, Berkoff et al. found that there was no significant difference in Time Domain and Frequency Domain HRV values between the endurance athletes and power athletes for both genders. The aerobic athlete group consisted of runners training and competing in 800m or longer while the power group included sprinters and athletes competing in field events that require more anaerobic training such as weight training and sprinting. From the results, they concluded that aerobic and anaerobic training leads to similar responses in Heart Rate Variability.

The study hypothesized that the lack of differences in HRV may be based on “autonomic benefits of anaerobic training.” It is possible that the autonomic cardiac changes that result from anaerobic training are similar to those seen with aerobic training. The researchers did note that although they did attempt to categorize the athletes into aerobic events and power events, all athletes’ training incorporates degrees of both aerobic and anaerobic systems.

There was no significant difference in Time Domain and Frequency Domain HRV values between the endurance athletes and power athletes for both genders. They concluded that aerobic and anaerobic training leads to similar responses in Heart Rate Variability.

Power sports require a degree of aerobic fitness. Intense muscle contraction uses anaerobic energy first and then is assisted by aerobic energy. Any activity that requires more than one rep is affected by the regeneration and energy pathways that the body’s aerobic systems provide. This means that anaerobic sports still require some aerobic fitness at performance levels.

If you are a power athlete, to ensure that you are not missing out on potential performance, it may be prudent to experiment with increasing aerobic fitness levels until HRV is noticeably impacted and compare, all else relatively equal, if multi-rep performance is improved.

Be Careful

It is important to point out that elevated aerobic fitness can also have a downside. Since it has such a potent effect on Heart Rate Variability, it can actually mask underlying health issues when HRV is taken out of context. We have all heard the stories of endurance athletes that have dropped dead during a race or even while just going about their normal lives. Aerobic fitness does not make up for suboptimal nutrition, suboptimal sleep, or other negative lifestyle choices.

Since it has such a potent effect on Heart Rate Variability, it can actually mask underlying health issues when HRV is taken out of context.

While endurance sports do typically increase aerobic fitness levels, they can potentially go beyond the levels necessary for optimal health. In my experience, when transitioning from sedentary to active lifestyle, the majority of fitness increases also correlate with increases in health. However, when transitioning beyond a basic active lifestyle to a competitive sport, there is a threshold where increases in fitness do not necessarily correlate with increases in health.

Another thing to consider is that training for any sport can go beyond healthy if there is not adequate variety or proper recovery built into the training program. Training can have high systemic stress that is beneficial for progression unless overdone, in which case, there is an increased chance of over-training and risk of injury.

Takeaways

In general, increased aerobic and anaerobic fitness significantly increases Heart Rate Variability. This is because increasing activity level and fitness increases autonomic activity correlating with increased ability for the body to regenerate energy, repair tissue, and more capably respond to both physical and mental stress.

Fitness levels that are required for health improvements do not require high volume, repetitive endurance sport training. An active lifestyle consisting of light to moderate activity (either aerobic or anaerobic or both) has shown to be sufficient for health benefits to reverse age-related HRV decline. Improved fitness beyond an active lifestyle increases Heart Rate Variability indices but it is not clear if those increases correspond to improved health past fitness.

Next Up – Health Status & Medications

High levels of aerobic fitness can mask underlying health issues when comparing your HRV values to normative, age-range demographic values.

In Part 3: Health Status & Medications, we will cover how medications can also mask health status. We will also cover the effects of health conditions, inflammation and immune system function in relation to Heart Rate Variability.